The Golden Poison Frog (Phyllobates terribilis) is a poisonous frog species belonging to the Dendrobatidae family, attracting attention in both scientific studies and the general public due to its venom. This species has a limited habitat, particularly in humid tropical forests along Colombia's Pacific coast. Known for its striking golden-yellow color, this species produces batrachotoxin, a powerful biotoxin, as a defense mechanism. These frogs are an important research topic in herpetology, toxicology, and conservation biology, both for their toxin biochemistry and their ecological significance. Below, the morphology, distribution, ecology, toxin properties, and conservation status of the Golden Poison Frog are presented systematically.

Morphological Features and Systematic Position

Physical Structure

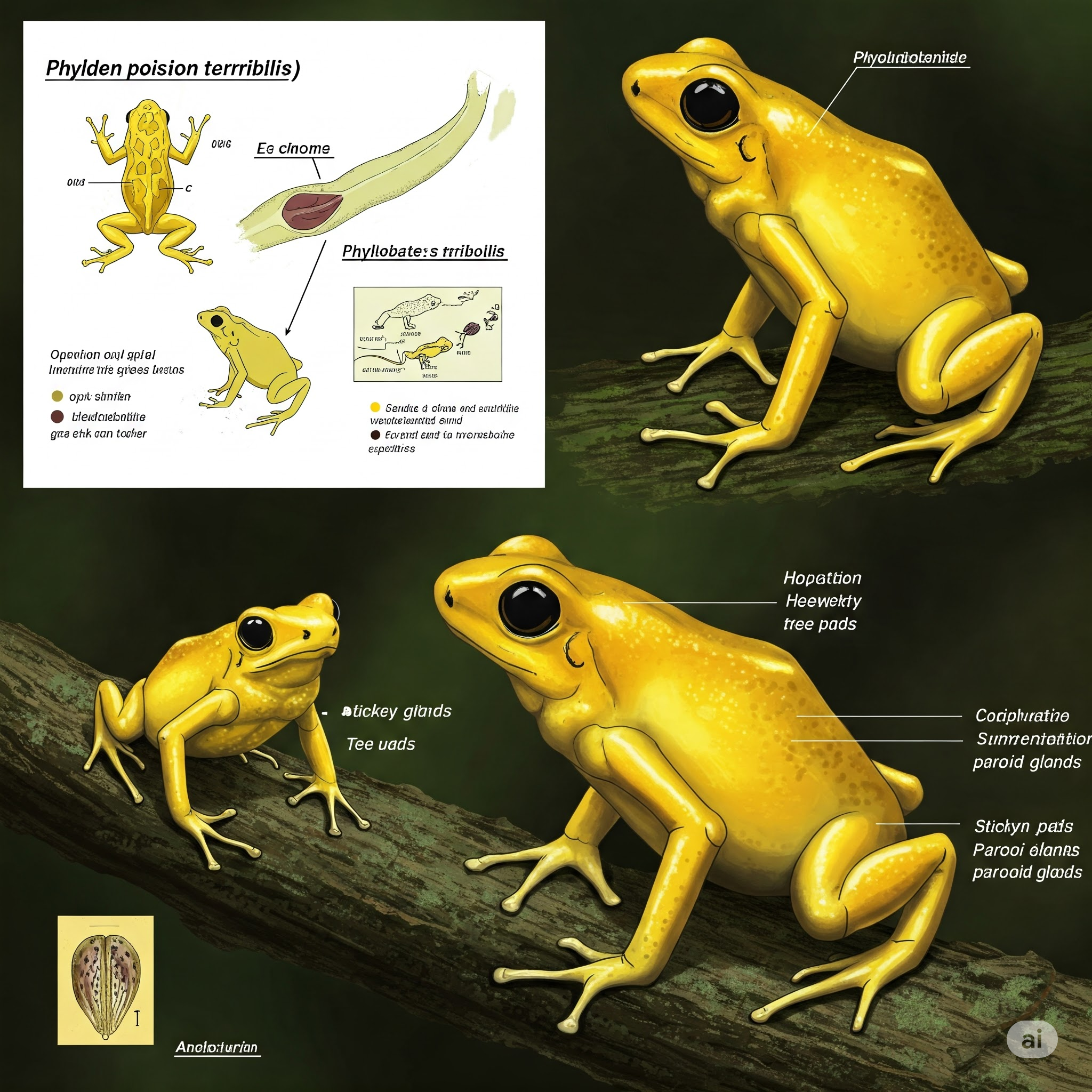

The Golden Poison Frog is one of the largest and most toxic species within the Dendrobatidae family. Adult individuals typically measure 47–55 mm in length, with females being slightly larger than males. Its skin is smooth and can be bright, usually golden yellow, orange, or greenish-yellow. These colors have evolved to signal its toxicity to potential predators through a biological phenomenon called aposematism. Its eyes are prominent, irises are dark, and the body generally has a compact structure.

Color Morphs

Phyllobates terribilis is notable for its distinct color variations observed in different geographical populations. Golden-yellow individuals are typically found in the La Brea region, while greenish-yellow individuals are found in the Quebrada Guangui region. These morphs show evolutionary differences in terms of both pigmentation and adaptation to local ecological conditions.

Taxonomic Classification

The Golden Poison Frog belongs to the phylum Chordata, class Amphibia, and order Anura. The genus Phyllobates, under the Dendrobatidae family, harbors highly toxic species. Phyllobates terribilis is the most venomous species of the genus, and intraspecific genetic differences are still a subject of phylogenetic research.

Golden Poison Frog Physical Structure (Generated by Artificial Intelligence)

Ecology, Habitat, and Life Cycle

Geographical Distribution

Phyllobates terribilis naturally lives in a limited area only in western Colombia, in the Cauca and Valle del Cauca departments. This species is found in tropical rainforests located approximately 100–200 meters above sea level. Annual rainfall can reach 5000 mm, and therefore, the frogs' habitat consists of ecosystems with high humidity and dense vegetation.

Habitat Characteristics

This species is found in low-altitude forested areas characterized by moist leaf litter, moss-covered rocks, and short shrub formations. The frogs are active throughout the day, showing intense activity particularly in the morning hours. They live on the ground surface and are usually hidden under large leaves or around moist stones. The limited natural habitat range makes the species vulnerable to environmental changes.

Feeding and Larval Development

The Golden Poison Frog primarily feeds on small ant species, mites, and termites. These small invertebrates, located at the lower levels of the food chain, are directly related to the frogs' ability to synthesize toxins. These frogs do not produce batrachotoxin directly; they accumulate toxins in their bodies by obtaining them from certain insect species found in nature. Females lay their eggs under leaves, and the larvae that hatch from the eggs are carried by males to puddles. After the development process is complete, young individuals transition to terrestrial life.

Golden Poison Frog Feeding (Generated by Artificial Intelligence)

Toxic Properties and Batrachotoxin

Batrachotoxin Definition

The primary defense mechanism of Phyllobates terribilis is an extremely toxic alkaloid called batrachotoxin. This neurotoxin permanently keeps sodium ion channels open, disrupting the function of nerve and muscle cells. As a result, severe physiological effects such as cardiac arrest, paralysis, and death occur in exposed organisms. Batrachotoxin was discovered in the 1960s by John W. Daly, and its molecular structure has been described in detail.

Toxicity Level

The amount of toxin secreted by an individual Phyllobates terribilis is approximately 700 micrograms, a quantity powerful enough to kill 20,000 mice. It can have potentially fatal effects on humans. These toxins are only found in frogs in their natural environment; this toxin level is not observed in individuals in captivity because the dietary elements necessary for toxin synthesis are not provided.

Ethnobotanical Uses

The indigenous peoples of Colombia have used the toxins of these frogs for hunting. Especially the Embera and Choco peoples smeared the toxins obtained from the frogs' backs onto arrow tips to incapacitate game animals. For this reason, the species is known as the "poison dart frog." However, this method of use is not through direct physical contact but by obtaining the toxin by heating the frogs or rubbing their skin.

Conservation Status and Threats

Natural Populations

The natural populations of the Golden Poison Frog are at risk due to their narrow habitat range and habitat destruction. Factors such as agricultural expansion, deforestation, illegal pet trade, and climate change threaten the species' living areas. The widespread expansion of palm oil plantations, in particular, has led to the large-scale destruction of tropical rainforests.

Conservation Status

Classified as “Endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), this species is also protected at the national level in Colombia. Its inclusion in CITES Appendix II means that its international trade can be conducted under certain rules. However, collecting individuals from the wild is largely prohibited.

Conservation Efforts

Various conservation programs are being carried out at both local and international levels. These programs emphasize habitat protection, cooperation with indigenous peoples, and scientific research. In addition, captive breeding programs are implemented in some zoos and research centers. Efforts to preserve genetic diversity and reintroduce the species to its natural habitat are ongoing.