Bu madde yapay zeka desteği ile üretilmiştir.

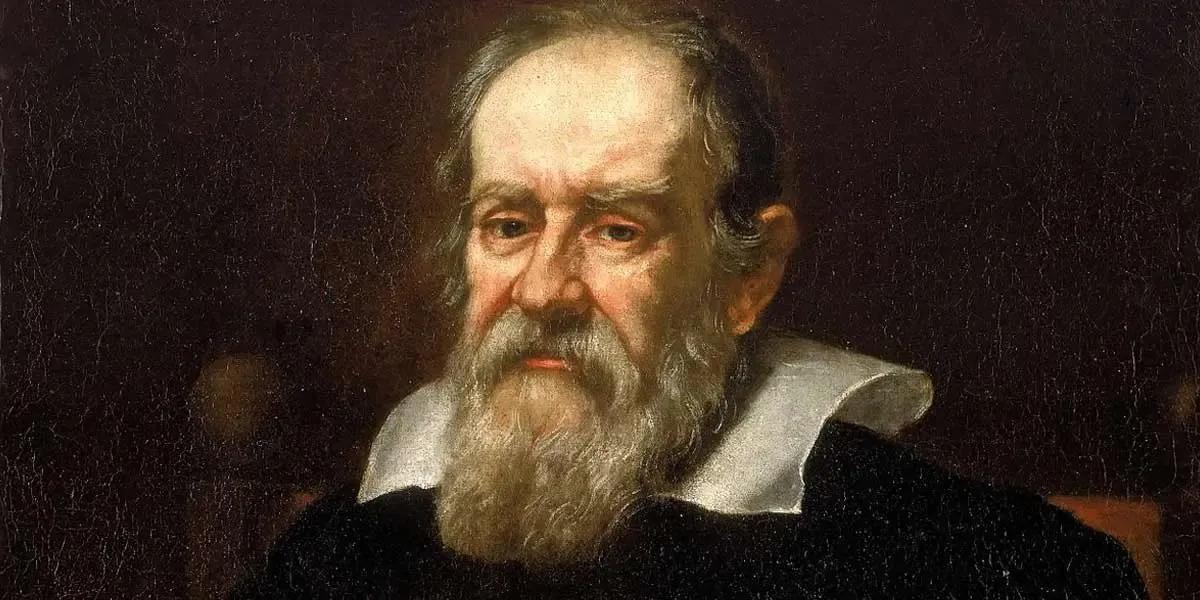

Galileo Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) is regarded as one of the most pivotal figures of the Scientific Revolution as an Italian mathematician, physicist, astronomer and philosopher. Using a telescope he developed, he observed the heavens and discovered the moons of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, sunspots and the rugged surface of the Moon; in physics, he conducted groundbreaking work on the motion of falling bodies, the laws of the pendulum and the foundations of mechanics. His defense of Copernicus’s heliocentric theory led to conflict with the Catholic Church and resulted in him spending the final years of his life under house arrest. Galileo’s empirical approach laid the foundation for modern science and earned him the title “Father of Modern Science.”

Galileo was born on 15 February 1564 in Pisa, Italy, within the Duchy of Florence. He was the eldest of six children. His father, Vincenzo Galilei, was a renowned musician and music theorist; his mother, Giulia Ammannati, came from a family engaged in textile trade in Pisa. The family moved to Florence in 1574, where Galileo began his formal education. He first received instruction from private tutors and later studied at the Camaldolese monastery in Vallombrosa. Although he considered taking religious vows, he ultimately abandoned this path.

In 1581, at the age of 16, Galileo enrolled at the University of Pisa to study medicine. However, he soon became fascinated by mathematics and physics. He attended lectures based on the dominant Aristotelian worldview. Due to financial difficulties, he left the university in 1585 without obtaining a degree. He supported himself by giving private mathematics lessons in Florence and Siena, during which he established connections with leading mathematicians. In 1589 he began teaching mathematics at the University of Pisa; in 1592 he became professor of mathematics at the University of Padua in the Republic of Venice.

In Padua, Galileo met Marina Gamba. Although they never married, they had three children together: Virginia (1600), Livia (1601) and Vincenzo (1606). Due to financial and social concerns, Galileo did not enter into a formal marriage with her. Fearing his daughters would be unable to secure advantageous marriages, he placed them in the San Matteo Convent near Florence during their adolescence. Virginia, after becoming a nun, took the name Maria Celeste and maintained a close relationship with her father; Livia took the name Arcangela. Vincenzo’s birth was later legitimized, and he also became a musician.

During his 18 years in Padua, Galileo conducted extensive research on mechanics. In his work De Motu (On Motion), written in the 1590s, he refuted Aristotle’s claim that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones. He demonstrated that falling bodies accelerate at the same rate and would reach the ground simultaneously in the absence of air resistance. He also studied the motion of pendulums and discovered that their period depends solely on their length, not their weight (isochrony). These findings were refined and published in his 1638 work Two New Sciences, which established the law of free fall as one of the fundamental principles of modern physics.

Galileo sought to describe motion mathematically and used inclined plane experiments to relate acceleration to time. He also developed the concept that an object in motion would continue moving indefinitely in a frictionless environment (inertia); this became the foundation of Newton’s first law of motion. Two New Sciences, which addressed both the structure of matter and the laws of local motion, represents the pinnacle of Galileo’s career.

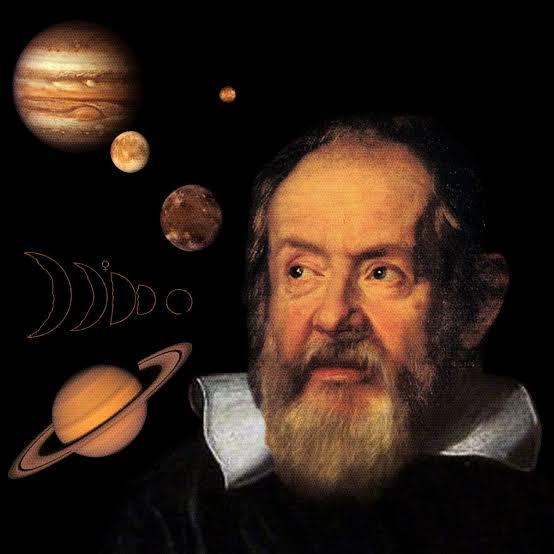

In 1609, upon hearing of the invention of the telescope in the Netherlands, Galileo improved upon the design and constructed an instrument capable of 33x magnification. Using this telescope, he made groundbreaking astronomical observations. In his 1610 publication Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), he revealed that the Moon’s surface was mountainous and cratered, that Jupiter had four large moons (now known as the Galilean moons), and that Venus exhibited phases similar to those of the Moon. By observing sunspots, he demonstrated that the Sun rotates and is not perfect. These findings shattered Aristotle’s belief that celestial bodies were perfect and unchanging and provided strong support for Copernicus’s heliocentric model.

Galileo dedicated his discoveries to the powerful Medici family of Tuscany, naming Jupiter’s moons the “Medicean Stars.” This strategy secured him the position of “Chief Mathematician and Philosopher” at the Medici court in Florence in 1610.

Galileo’s advocacy of the Copernican theory brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church. At the time, the Church endorsed Ptolemy’s geocentric model of the universe. In a 1613 letter to his student Benedetto Castelli, Galileo argued that the Copernican theory did not contradict Scripture; he expanded this view in a 1615 letter to the Grand Duchess Christina. He maintained that nature and the Holy Scripture represented different domains of truth and that scientific findings could inform the interpretation of religious texts.

In 1616, the Church placed Copernicus’s work De Revolutionibus on the Index of Forbidden Books and ordered Galileo not to “defend, teach or hold” the heliocentric theory. Galileo complied for seven years. However, after his friend Cardinal Maffeo Barberini became Pope Urban VIII in 1623, Galileo felt emboldened and published his 1632 work Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. The book presented a dialogue between three characters discussing the heliocentric and geocentric models, but clearly favored the Copernican view. This provoked the Church’s response.

In 1633, Galileo was tried before the Inquisition in Rome and found “vehemently suspect of heresy.” Under threat of torture, he was forced to publicly recant his theories and sentenced to indefinite imprisonment; this was immediately commuted to house arrest. While confined to his villa in Arcetri near Florence, where he was forbidden from receiving visitors or publishing works in Italy, Galileo managed to have Two New Sciences published in Holland in 1638.

During his years under house arrest, Galileo lost his eyesight and his health deteriorated. The death of his eldest daughter, Maria Celeste, in 1634 deeply affected him. Nevertheless, he continued his scientific work and completed his final book, Two New Sciences, summarizing his ideas on mechanics and motion. On 8 January 1642, at the age of 77, he died in Arcetri from heart palpitations and fever. Due to the Church’s objections, he was initially buried in an unmarked grave; in 1737 his remains were reinterred in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence.

Galileo’s work was decisive in the birth of modern science. His integration of the experimental method and mathematics into the study of nature influenced later scientists such as Newton. His astronomical discoveries accelerated the acceptance of the heliocentric model. The Church lifted its ban on works supporting the Copernican theory in 1758 and in 1992 Pope John Paul II expressed regret over the handling of Galileo’s case.

Galileo earned a pivotal place in history through his scientific courage, innovative thinking and relentless pursuit of understanding the universe. His legacy endures not only through his discoveries but also through the methodological approach that shaped the progress of science.

Henüz Tartışma Girilmemiştir

"Galileo Galilei" maddesi için tartışma başlatın

Early Life and Education

Family Life

Scientific Work and Discoveries

Physics and Mechanics

Telescope and Astronomy

Conflict with the Church

Final Years and Death

Legacy