The Battle of Domokos on 17 May 1897, was the most decisive stage of the 1897 Ottoman-Greek War. The war broke out between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Greece, mainly due to the unrest on the island of Crete and Greece's expansionist policies in line with Megali Idea. Although the Ottoman army achieved a military victory in this battle, it lost its advantage on the field as a result of the subsequent negotiations.

Ottoman Army's Assault (AI-Generated.)

Causes and Course of the Battle

By the end of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire had suffered a significant loss of power due to internal rebellions and interventions. Greece, which gained its independence in 1830, took advantage of this weakness and increased its demands on Ottoman territories. The underlying idea behind these demands was the Megali Idea, shaped by a historical perception stretching from Ancient Greece to modern Greece. The rebellions sparked by Greeks on the island of Crete and activities supported by armed gangs are evaluated in this context. The general peace maintained by the Ottomans on the island began to systematically deteriorate with the tensions experienced from 1866 onwards.

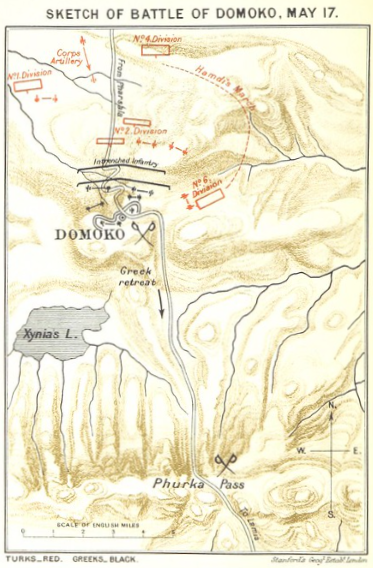

Domokos Battle Plan 1 (Flicker: British Library)

During the war, the Ottoman land forces outnumbered the Greek forces; approximately 40,000 Ottoman troops fought against about 20,000 Greek troops. However, Greece had an advantageous position in terms of defensive lines and terrain. With the start of the war on 16 April 1897, the Ottoman army quickly gained the upper hand on the Thessaly front. Ottoman forces under the command of Ethem Pasha passed through the Milano Pass and captured strategic points such as Valestin, Çatalca, and Galos.

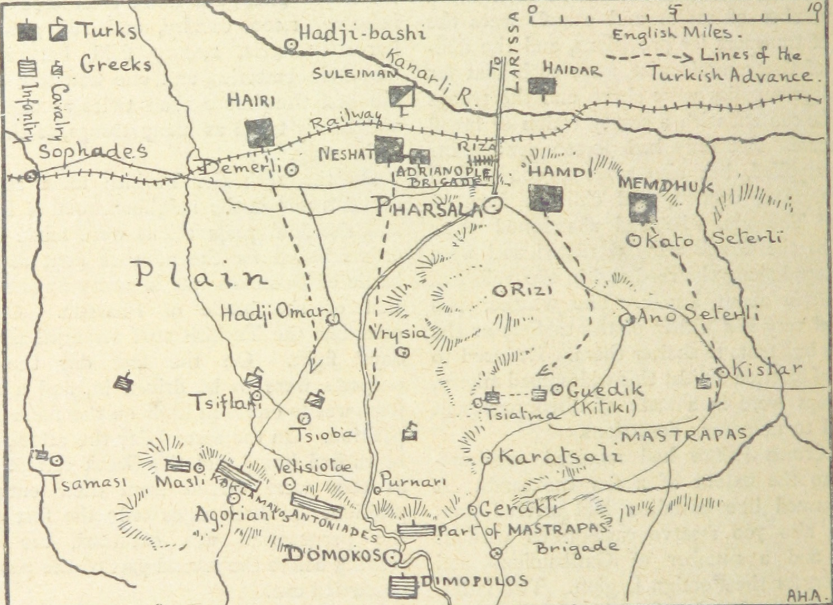

On the morning of May 17, the Ottoman army moved in various groups; on the right flank, Hayri Pasha advanced towards Tsioba village, while Neşet Pasha, to his left, advanced towards Domokos along the main road. In the center, Hamdi Pasha, and on the left flank, Mahmud Pasha were positioned to target the Greek right.

Haydar Pasha commanded the support forces following Hamdi Pasha. In the morning, Hayri Pasha's troops encountered a small Greek cavalry unit at Tsioba. Overestimating the size of the force, Hayri Pasha launched a cautious attack, and the village was captured only after an hour of fighting. Hayri Pasha's slow advance necessitated Neşet Pasha's waiting. At the same time, Hamdi Pasha's troops clashed with the Greek 4th Division under Colonel Mastrapas and advanced with artillery support. Memduh Pasha's troops also faced Greek troops.

Domokos Battle Plan 2 (Flicker: British Library)

During the day, the Ottoman troops approached the Greek defensive lines on the plain in front of Domokos. While Neşet Pasha's artillery bombarded the Greek positions, the infantry advanced to within 400-600 yards. However, in the evening, the artillery fire subsided, and the Greek lines largely held their ground. At 11 pm, Edhem Pasha was informed by a report from Hamdi Pasha. According to this, Hamdi and Memduh Pasha's troops had approached the Greek right flank and reached a position from which they could target the Greek right or rear. Edhem Pasha ordered Hamdi Pasha to break the Greek right flank with an attack the next morning, and Memduh Pasha to cut off the Greek army's retreat line via the Furka Pass.

Faced with the effective offensive of the Ottoman army, the Greek army could not withstand any longer and began to retreat in a rout. As a result, the Ottoman army, numerically superior, defeated the Greek forces in the Battle of Domokos between May 17-20, 1897, capturing Domokos, Ermiye, and the Furka Pass. With this victory, the Greek army was largely dispersed, and the way for the Ottomans became almost unobstructed.

Diplomatic Developments and Treaty

Despite the military success, the Ottoman Empire suffered a loss in the diplomatic arena. With the intervention of the Great Powers, an armistice was declared on May 19, 1897, followed by the signing of the Treaty of Istanbul on December 4, 1897. With the treaty, Thessaly was returned to Greece, and the Ottomans received only four million Ottoman liras in compensation. The territories captured by the Ottoman Empire during the war were largely returned; this situation showed that the war did not end in favor of the Ottomans at the negotiating table.