Desmodus rotundus, commonly known as the common vampire bat, is one of three bat species in the Neotropical biogeographical region that feeds exclusively on blood, and its hematophagous lifestyle involves many unique evolutionary adaptations. Its body mass, ranging from approximately 20–43 g, sharp chisel-shaped upper incisors, strong sense of smell, and infrared-sensitive upper lip sensors support the species' unique trophic strategy. This colonial species has also been extensively studied for its rare mammalian behaviors such as social cooperation and reciprocal food sharing.

Taxonomy, Morphology, and Phylogenetic Context

Taxonomic Position and Evolutionary Relationships

Desmodus rotundus is the type species of the subfamily Desmodontinae, within the family Phyllostomidae of the order Chiroptera. The hematophagy character it shares with other members of the subfamily, Diaemus youngi and Diphylla ecaudata, emerged in the Middle Miocene (approximately 18–15 Ma) according to molecular clock analyses. Phylogenetic models performed on mitochondrial cyt-b, nuclear RAG2, and ultraconserved sequences indicate a rapid increase in positive selection pressures during the transition from insectivorous-frugivorous feeding to blood-feeding in the Neotropical ancestors of the genus Desmodus.

Morphological Features

The upper incisors, which provide high penetration power for blood acquisition, maintain their sharpness by self-sharpening with their enamel-free anterior surfaces. The nasal structure contains trigeminal receptor plates sensitive to infrared perception; this adaptation provides the ability to detect capillary-dense regions. Single-row papillae on the tongue surface facilitate the laminar flow of aspirated blood. Strong anticoagulants (desmoteplase, desmolaris) and host platelet aggregation inhibitors are synthesized in the salivary glands. In the skeletal system, the shortened radius-ulna and long hind limbs are modified to support body weight during blood feeding.

Distribution and Habitat Preferences

The species has a wide range extending from northern Mexico to Uruguay. It is most commonly found in tropical evergreen forests, semi-open savannas, and human-made shelters (old mine adits, bridge arches, barns). Colony density significantly decreases in regions where the annual average temperature drops below 10 °C; because prolonged low temperatures restrict both the probability of finding blood and digestive efficiency. Colonies consist of an average of 20–100 individuals, where female individuals exhibit natal philopatry and males show dispersive behavior.

Mother and Offspring Feeding (Generated by Artificial Intelligence)

Behavioral Ecology, Social Dynamics, and Feeding Strategies

Hematophagous Feeding Mechanisms

D. rotundus typically commences feeding activity within the first three hours of the night. It approaches the target by sensing temperature differences in livestock through its conical homological flight pattern. It creates a superficial incision of 3–5 mm in length on the skin with its incisors, then sucks an average of 7 ml of blood per minute using negative pressure created by its tongue and pharyngeal muscles. Desmoteplase, a plasminogen activator found in saliva, rapidly dissolves fibrin clots, sustaining blood flow for up to 30 minutes. In the digestive system, a high nitrogen load has led to ureotely instead of uricotelic excretion, and strong solute reabsorption has developed in the kidneys.

Social Organization and Behavior

In the colony, inter-female solidarity is defined by allogeneic milk donation and reciprocal food sharing. Starving individuals receive regurgitated blood orally from kin or partners who have previously donated blood to them; this behavior strengthens inter-individual social networks. Recognition of familiar individuals and partner-specific vocal signatures have been detected via ultrasonic calls (10–40 kHz). Social grooming not only reduces parasitogenic load but also reinforces social bonds. Male individuals periodically enter and exit core groups of females; this temporary membership increases sperm competition while balancing gene flow.

Sleeping Behavior - Pixabay

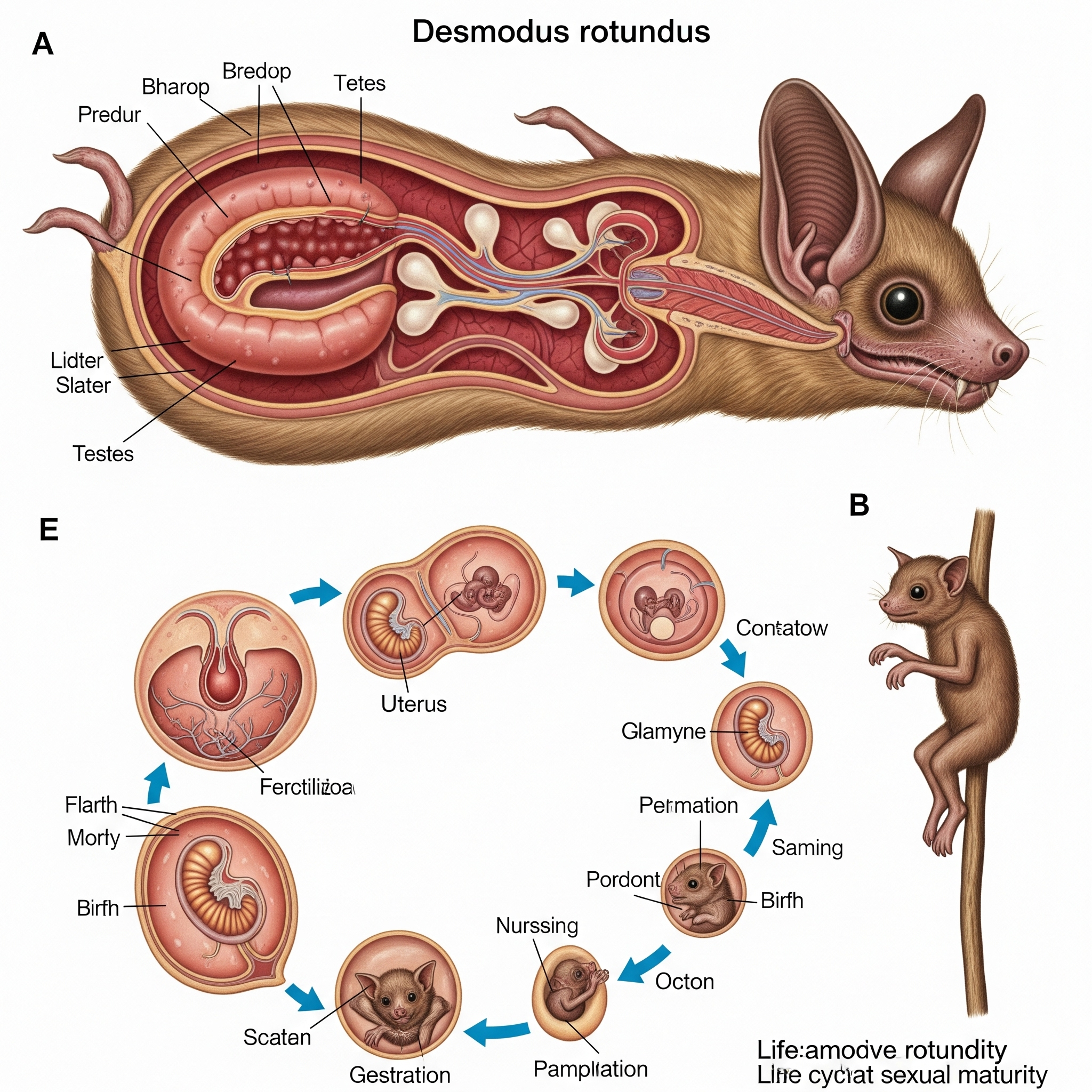

Reproductive Physiology and Life Cycle

The annual reproductive cycle is year-round in populations near the equator, while in subtropical regions, it shows a single peak parallel to the rainfall regime. Females give birth to 1, rarely 2, offspring after a 9-month gestation. The ratio of neonatal mass to maternal mass is around 22%; this high value for mammals is thought to shorten the lactation period. Sexual maturity is reached at 9 months for females and 10–12 months for males. Although the average lifespan in nature varies between 9–12 years, individual tracking has reported records of over 20 years.

Reproductive Physiology and Life Cycle (Generated by Artificial Intelligence)